Let's start with how human cells normally defend themselves against viruses. One way this works is through antibodies. These large, Y-shaped proteins are produced by plasma B cells, a type of white blood cell. Antibodies attach to certain pathogens, effectively tagging them for further attack by the immune system. However, we only make antibodies after being exposed to a pathogen. If the pathogen mutates, or if you're exposed to a new one, antibodies won't work.

Another way our cells defend themselves is by using a certain protein (called Protein Kinase R) to identify the products of viruses inside our cells. When that happens, the cells produce Interferon, which signals the cell and its neighbors to reduce the rate at which they create new proteins. Doing that helps slow the virus down. In addition, cells also try to commit suicide, through a natural process called apoptosis.

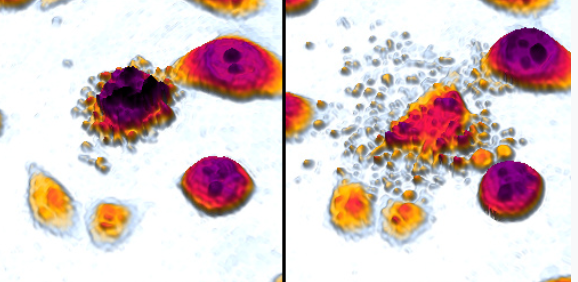

Apoptosis results in a cell "imploding." By that I mean that it breaks into a number of small pieces, which can then be ingested, absorbed and destroyed by scavenger cells. You can see the small pieces in the images below of a cell undergoing apoptosis:

An average human adult loses 50 to 70 billion cells to apoptosis every day. Those old or damaged cells are then simply replaced by new, healthy ones.

By contrast, in necrosis, the opposite of apoptosis, a cell's outer membrane breaks, and its interior just spills or "explodes" into the surrounding area. While apoptosis is considered normal by the immune system, necrosis generates all kinds of alarms ("danger signals"), resulting in inflammation and other actions by the immune system.

Unfortunately, viruses have also evolved a number of mechanisms that interfere with these defenses. For example, they can prevent Interferon from being created, or apoptosis from happening, or both.

The way VTose works is by providing a direct path from virus detection to apoptosis. Normally, there are multiple biochemical steps between virus detection and the apoptosis trigger. Viruses tend to interfere very early in that chain of events. In contrast, VTose triggers the process very late in the chain. By avoiding those first, early steps, there's very little the virus can do to defend itself.

The detection target and mechanism are actually the same one used by the body: (part of) the PKR protein attaches to long segments of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which are produced only by viruses, and not in healthy human cells.

To summarize, it works like this:

dsRNA --> detected and attached by VTose --> triggers activation of apoptosis --> cell death by "implosion" --> cell fragments are scavenged and removed